In the acclaimed 1982 film “Sophie’s Choice,” Meryl Streep won Best Actress for her role as a Polish immigrant during World War II. Upon arriving at the Auschwitz concentration camp with her two children, she was asked a question by a Nazi soldier, the answer to which would haunt her for the rest of her life. Had the solider asked her to decide between being sent to the gas chamber herself or having her two children put to death, the answer would have been easy. But instead, he asked a more gut-wrenching question: Which of her two children would be sent to the gas chamber and which would go on to the labor camp. The soldier made it clear that unless she made a choice, both children would be killed. She ended up choosing her son Jan to go the labor camp while her daughter Eva was sent to the gas chamber. While the German soldier’s question was unimaginably cruel, it does highlight for us the importance of choice and the consequences of the choices we make. Welcome to today’s post on the science of choice architecture and the implications for effective retail merchandising.

In the U.S., choice remains headline news during the pandemic as the battles rage on between those who favor mask and vaccine mandates and those who argue for freedom of choice. The fact is that choice is baked into our DNA. Free will, or the unalienable right to choose, is a fundamental design principle of God’s creation for mankind. While He could have programmed men and women to automatically choose to believe in Him, instead He left that choice up to us, and each of us will one day reap the eternal consequences of that decision.

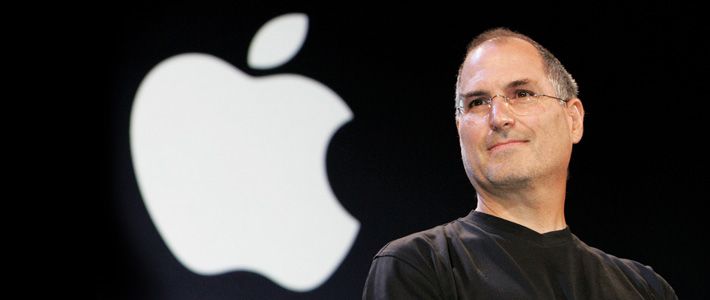

Many companies suffer from product proliferation which inevitably leads to unnecessary complexity and lack of focus, while also stifling innovation. Upon his return to Apple in 1997, Steve Jobs famously slashed Apple’s product line by 70%, choosing to focus on 4 core products. At the time, the company was losing over $1B and was 90 days from insolvency. Jobs’ bold move restored the company to profitability, introduced a maniacal focus on quality, inculcated a culture of discipline, and unleased decades of extraordinary innovation that brought to market a stunning assortment of game-changer products that have enriched our lives. After a new product introduction, Apple’s goal was always to make that product obsolete as quickly as possible by replacing it with something new and better.

Like Apple prior to Jobs’ return, many retailers and brands are guilty of product proliferation. Do consumers really need a choice of 27 varieties of Crest toothpaste or 25 formulations of Head & Shoulders shampoo? Will shoppers fret if they are not offered 40 different styles of sunglasses? How much choice is enough? At what point does too much choice result in choice overload or choice exhaustion?

- When it Comes to Choice, Less is More– More is better is the mantra of Capitalism. Since 1975, the number of products in an average U.S. supermarket has more than tripled from less than 9,000 to more than 28,000. In an attempt to maximize market share and profits, CPG companies and retailers have collaborated to offer an impressive range of product variations- 9 varieties of Pringles potato chips, 11 flavors of Cheerios, 74 varieties of Campbell’s Soup. Many retailers believe that carrying a deep assortment of products is critical for attracting and retaining customers. However, in his book The Paradox of Choice, psychologist and social theorist Barry Schwartz argues that too much choice not only leads to fewer sales but also lower satisfaction among buyers. Increased choice in retail merchandising leads to escalation of expectations and choice overload which can impair a shopper’s ability to make a decision and to feel good about it.

He points to one study in which there were 2 different jam tasting displays set up in a gourmet food store. One display offered 6 jams while the other offered 24. The study showed that 30% of shoppers who tasted from the 6-jam display made a purchase compared to only 3% who were given a choice of 24 jams.

While the rule of less choice generally holds, there are nuances. For example, research shows that if a product is intended for pleasure, people prefer more choice because they believe that what pleases them differs greatly from what pleases other people. Conversely, if the product is intended to meet a functional need, most people believe their preferences align more closely with others, and they therefore are satisfied with fewer choices.

- Some Choice Matters– While too much choice can create anxiety, indecision, and dissatisfaction among shoppers, not to mention the inconvenience related to the extra time required to evaluate options, we know that consumers overwhelmingly prefer more than 1 choice. Many consumers start their product search online, and 64% of clicks go to the first 3 organic listings in a search result, while 70% of users stick to the first page of search results. This again supports the notion that people want choice but not too much.

Offering customers a single product gives them a binary choice. Either they buy it or they don’t. They may be left wondering if they are getting a good deal or if there might be another product out there that is a better fit. In short, 1 size doesn’t always fit all, and a single product choice can comprise a consumer’s sense of control and limit the perception of choice, thereby reducing buyer satisfaction.

The trick is finding the sweet spot between too much choice and not enough choice.

- How to Create Choice Architecture– Most people who order wine at a restaurant don’t pick the cheapest, nor do they choose the most expensive of the options offered. Most will choose what is familiar to them and what they like, but if they are unfamiliar with the brands offered, they usually are guided by price and will choose the second of third most expensive option. Ordering wine at a restaurant is a classic example of choice architecture and is instructive for brands.

The idea of choice architecture is to create a good, better, best set of choices or a gold, silver, and bronze package. This structure provides a framework to help the consumer understand where they fit within the product ecosystem. It empowers the consumer by giving them control and permission to choose while building in a sense of escalation into the decision process.

Creating a winning choice architecture typically starts with identifying a set of benefits of your product line. For most companies the silver product is the profit engine. It might offer 7 of the 10 core benefits of your product line and is typically chosen by the majority of consumers. The gold product would offer additional benefits but should be significantly more expensive. Not only will that help you capture the high-end customers, but it will make the buyers of your silver product feel like they are getting a deal. Even if you don’t get many takers, offering a lower-end bronze product that is significantly cheaper helps to frame the silver product and provides a hook for the value-oriented shoppers.

Choice architecture gives consumers the sense that they are making an informed decision, a decision that is right for them.

***********

In conclusion, whether you are a retailer developing your merchandising strategy or are a brand/product manufacturer trying to decide how many SKUs to include on your POP display, you are likely to achieve best results if you focus on your best sellers rather than your entire product line as long as your SKU count is sufficient to create the choice and empowerment necessary to trigger buying behavior and lead to buyer satisfaction.

Jim Hollen is the owner and President of RICH LTD. (www.richltd.com), a 35+ year-old California-based point-of-purchase display, retail store fixture, and merchandising solutions firm which has been named among the Top 50 U.S. POP display companies for 9 consecutive years. A former management consultant with McKinsey & Co. and graduate of Stanford Business School, Jim Hollen has served more than 3000 brands and retailers over more than 20 years and has authored nearly 500 blogs and e-Books on a wide range of topics related to POP displays, store fixtures, and retail merchandising.

Jim has been to China more than 50 times and has worked directly with more than 30 factories in Asia across a broad range of material categories, including metal, wood, acrylic, injection molded and vacuum formed plastic, corrugated, glass, LED lighting, digital media player, and more. Jim Hollen also oversees RICH LTD.’s domestic manufacturing operation and has experience manufacturing, sourcing, and importing from numerous Asian countries as well as Vietnam and Mexico.

His experience working with brands and retailers spans more than 25 industries such as food and beverage, apparel, consumer electronics, cosmetics/beauty, sporting goods, automotive, pet, gifts and souvenirs, toys, wine and spirits, home improvement, jewelry, eyewear, footwear, consumer products, mass market retail, specialty retail, convenience stores, and numerous other product/retailer categories.